Janet Yellen’s call last month for the World Bank to “think well beyond the status quo” to help deliver the trillions of dollars needed to tackle multiple global crises made the US Treasury secretary part of a growing chorus of western economic officials urging the bank to lend more by relaxing its capital requirements.

Over the past year, development economists and US government advisers have leaned on multilateral development banks (MDBs) to borrow more — even if it means foregoing their triple-A credit ratings — to meet a host of challenges, ranging from food crises to climate change, affecting some of the world’s poorest countries.

The pandemic and the fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine have added to the pressure on institutions, such as the World Bank and other MDBs, that were already struggling to provide the finance needed to meet UN Sustainable Development goals.

“We never foresaw that we would have to deal with almost permanent crises over the past two years,” said Axel van Trotsenburg, the World Bank’s managing director of operations. “Once this crisis is over, we will not be able to lend at [the] types of levels [we are at present].”

MDBs were designed to finance long-term development projects and to tackle short-term crises on a case-by-case basis. However, the multiple crises the global economy is now facing are stretching balance sheets to the maximum.

One board member at a multilateral lender said: “We cannot say the multilaterals are doing too little — it is already an enormous effort — but the situation is bad and we are risking not one but two lost decades for development.”

Munir Akram, Pakistan’s permanent representative at the UN, has highlighted the scale of the challenge facing MDBs. Akram said last month that developing countries had received only about $100bn of the estimated $4.3tn of finance they would need to fund their recovery from the pandemic.

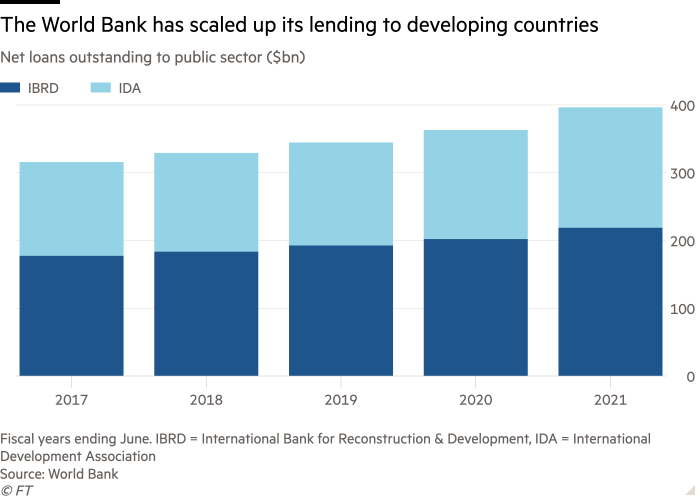

The World Bank’s lending capacity has already risen sharply over recent years.

In 2018 and 2019, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Development Association — the group’s divisions that lend to governments in middle-income and low-income developing countries, respectively — had a combined lending capacity of about $88bn.

In 2020 and 2021, that figure rose to $135bn, a more than 50 per cent increase. In April, the bank promised a combined IBRD and IDA lending package of $170bn over the coming 15 months, delivering another surge in the bank’s activities.

This is without counting two other World Bank divisions, the International Finance Corporation and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, which provide finance to the private sector in developing countries, and which together took lending capacity for 2020 and 2021 to about $204bn.

Nevertheless, much more is needed. Yellen spoke last month of the “trillions and trillions” of dollars required to fight climate change alone, and suggested the World Bank should change its mandate to be able to mobilise more private sector money.

Chris Humphrey, a specialist in development finance at the Overseas Development Institute, a UK think-tank, argued early in the pandemic that the six biggest lenders, with a combined loan portfolio in 2019 of $463bn, could have lent an additional $745bn just by including their callable capital — a guarantee provided by shareholders that has never been called on by any MDB — when calculating their capital adequacy. On top of that, he argued, they could have lent an additional $1.3tn by accepting a one-notch downgrade in their credit ratings to AA+, with a negligible impact on their cost of borrowing.

The New Development Bank — set up in 2015 by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — has found its AA+ rating, one notch lower than triple-A, has only increased its borrowing costs by less than 0.15 percentage points.

The World Bank, however, is unwilling to lose a triple-A rating it describes as “the cornerstone of our financial model”. It has argued that lower ratings would leave the group able to deliver less lending rather than more, especially during times of crisis.

Nor is there a consensus among shareholders for the MDBs to become less risk-averse.

One person familiar with discussions on the issue at the G20 group of large economies said that, while some developing countries supported such changes, there was “more rather than less polarity” among members.

“The winners in the system are really afraid of change,” the person said. “There’s a ‘Chicken Licken’ response when they hear the words ‘rethinking capital adequacy’, that only the worst will befall us if we do anything different.”

With little immediate prospect of change at the MDBs, governments in developing countries have called on advanced economies to lend or otherwise share their special drawing rights, or SDRs — a form of IMF reserve asset of which the fund distributed the equivalent of $650bn last year as part of its coronavirus response — in order to plug lending gaps. But progress here, too, has been slow.

Richard Kozul-Wright, director of globalisation and development strategies at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, said failure by rich countries to move more quickly had caused irritation and frustration among many developing countries at the spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank this month.

“There is one mechanism that could really address the issue, and that is the hundreds of billions of dollars in unused SDRs,” he said. “But we are not using it. This is not a call for big reforms at the multilaterals. It’s a call to step up to the plate — please.”