This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Hello. Here’s the document we’ve been waiting for, the draft proposal to create flexibility in World Trade Organization rules to allow countries to waive patents on Covid-19 vaccines. It’s less than 900 words*, about the length of a Trade Secrets newsletter, quite concise for such a politically fraught subject. It was mooted more than 18 months ago and has been thrashed about in detailed talks since. And now, it seems, most of the governments that were negotiating it don’t want to take ownership of it. The text was discussed by ambassadors at the WTO on Friday and elicited a lot of questions but no enthusiastic agreement or outright opposition as yet. Like all the best WTO proposals it was punted off to another meeting. Today’s main piece looks at the rather dysfunctional politics of how we got here and what it means for the management of global trade in the era of the pandemic. Charted waters is on the state of German-UK trade post-Brexit.

*including footnotes

Get in touch. Email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

Not waiving but clowning

First, let’s canter extremely briefly through the details of the draft waiver, which I’ll discuss properly in a future newsletter. It’s a long way from the original proposal by India and South Africa for a super-wide loophole that would essentially remove protections in the WTO’s “Trips” intellectual property agreement for all kinds of IP (patents, copyright, trade secrets) for anything that might be used to treat or prevent Covid.

The draft text clarifies and potentially modestly expands existing freedoms for governments to override patents for Covid vaccines — but only vaccines, a potential widening to cover more drugs be discussed later. Some health campaigners argue it could actually make things worse by requiring countries to undertake complicated listing and notifications processes. Ultimately, if you believe IP is a serious problem with global Covid vaccine production, you’re highly unlikely to think this is the solution.

Even the only WTO member explicitly to have supported it, the EU, doesn’t try to claim it’s a radical rolling-back of IP, which Brussels says is unnecessary anyhow. It only applies to a subset of developing countries, and there’s a peculiar subplot whereby China is happy to be excluded from its benefits, having had no difficulty manufacturing and exporting vaccines in vast quantities, but wants the right to opt out voluntarily rather than have official criteria created that it fails to meet.

The politics surrounding the waiver are even less impressive than the thing itself. The Biden administration in the form of US trade representative Katherine Tai unexpectedly gave the proposal a big boost by declaring support for a waiver almost exactly a year ago. Many (including me) were quite excited at the time by the boldness. But it transpired that either the administration was disingenuously virtue-signalling or had, incredibly, failed to spot that the drugs industry might have views on trashing vaccine IP. It rapidly faced resistance from the EU, which at least had the guts to say publicly it was against a broad waiver, and from the pharmaceutical lobby activating its agents on Capitol Hill — see the intervention on page S9189 here from Senator Mike Lee of Utah.

The US eventually joined a small “Quad” negotiating group of four WTO members along with the EU, India and South Africa, but failed to come up with concrete proposals itself or make a strong argument publicly for a particular model. Accordingly, when a draft negotiating text (clearly already at an advanced stage of talks) was leaked in March, USTR was confronted by lawmakers and activists demanding to know what was being negotiated in their name.

Along with India and South Africa, which have run into opposition themselves for letting their original proposal be heavily watered down, the US has now got itself into the rather feeble position of letting a text go forward for general discussion among all WTO members without explicitly backing it. The situation has put WTO director-general Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala in the awkward position of having to put her name to it instead. The waiver is one of the few possible breakthroughs at the organisation’s big ministerial meeting in June, and (as you can see from the FT’s interview with her in March) Okonjo-Iweala is committing a lot of personal capital to it.

Rather too much, in fact, according to some health activists, whose criticism is turning a bit personal. Mohga Kamal-Yanni, senior policy adviser to the People’s Vaccine Alliance campaign, says: “There were high hopes that, under the leadership of an African woman, the WTO would finally broker more equitable outcomes in these kinds of disputes. But if this is the best deal that the WTO can deliver in a global pandemic, clearly rich countries still dominate the institution”. Ouch.

Not for the first time, the WTO’s members, particularly the US, are letting the system down. The Biden administration made a big splashy announcement last year without covering its home flank. It ended up caught between the progressive activists who have established a strong hold over US trade policy on the one side (I’ll look at this later in the week) and the drugs industry on the other. What else, exactly, did it expect?

The US publicly met the waiver proposal last week with a painfully non-committal response, a stance it also took in Friday’s meeting of ambassadors, where it said it was consulting domestically. But Washington looks weak if it doesn’t ultimately back it. If the US really objected they should have killed it at a much earlier stage in talks before it was leaked.

So what happens now? If the WTO members find some accommodation for China and make a few tweaks, there’s a reasonable chance it gets adopted. That would be a rare success for the WTO as an institution, or at least for its management. But it wouldn’t speak much for the courage or competence of the likes of the US in getting there.

As well as this newsletter, I write a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Wednesday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all my columns and previous newsletters too.

Charted waters

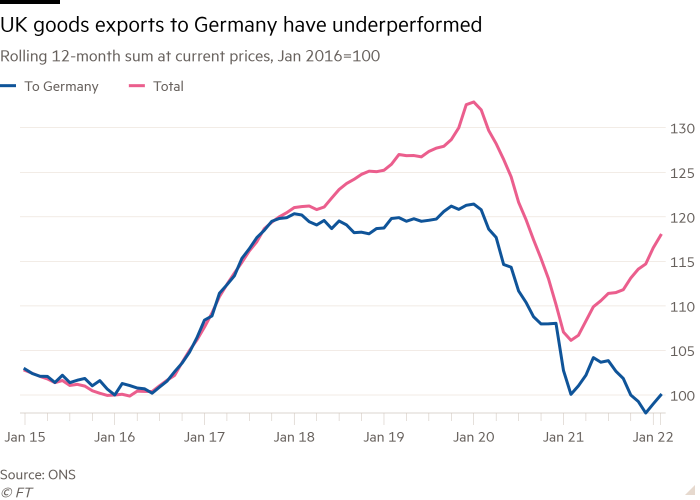

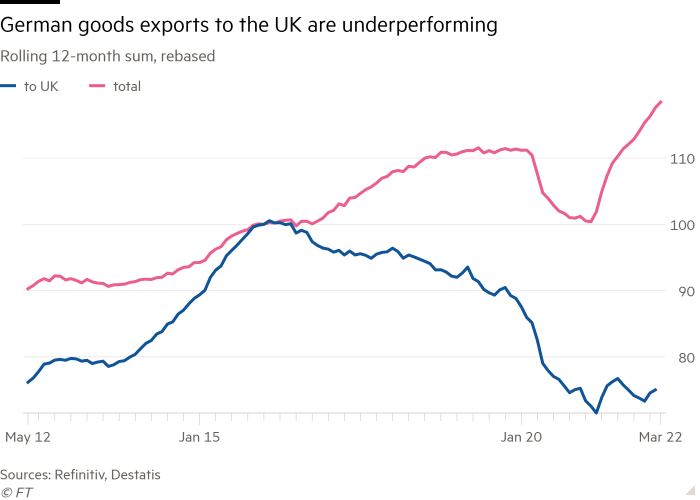

Two charts this week, to illustrate how the UK’s departure from the EU helps nobody when it comes to trade, as my colleagues Valentina Romei and Peter Foster explain in their excellent analysis.

Germany is just one EU trading partner for the UK, but it is by far the most important. Germany is Britain’s second-largest trading partner after the US, and trade between the two countries supports more than 500,000 jobs in the UK, according to official estimates.

Here is what happened to UK goods exports in the wake of the UK vote to leave the EU.

That would be bad enough. But as the chart below shows, Brexit has also damaged Germany through trade lost the other way.

Of course, new trade opportunities with other nations could eventually surpass what the UK has gained historically from trading with Germany. What has come to pass to date, however, is what had been predicted by economists all along. What these two charts reflect is the gradual decoupling of the UK manufacturing economy from the EU single market. (Jonathan Moules)

Trade links

The Washington Post reports that the White House is alarmed that a Department of Commerce probe into China circumventing solar panel tariffs is smothering the US domestic industry.

The plucky Faroe Islands (pop 53,800), a self-governing part of Denmark that is not in the EU, has legislated to impose sanctions against Russia, which would be the first time it has sanctioned any trading partner.

A long read by Politico lays out the tensions among different factions in the US administration over trade.

Elections in Northern Ireland have seen good results for parties supporting the post-Brexit Northern Ireland Protocol, so naturally the UK is threatening to tear the Protocol up. As it has before. And again before that. And again last year.