Experts are warning that the Eastern U.S. should prepare for another barrage of tropical storms this year. The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season is likely to be more active than average for the seventh year in a row, according to the latest prediction from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

There is a 70% chance that the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season, which starts on June 1 and ends Nov. 30, will bring 14 to 21 named storms, or storms with winds of 39 mph (63 km/h) or higher; six to 10 hurricanes with winds of 74 mph (119 km/h) or greater; and three to six major hurricanes, with winds of 111 mph (179 km/h), according to NOAA (opens in new tab).

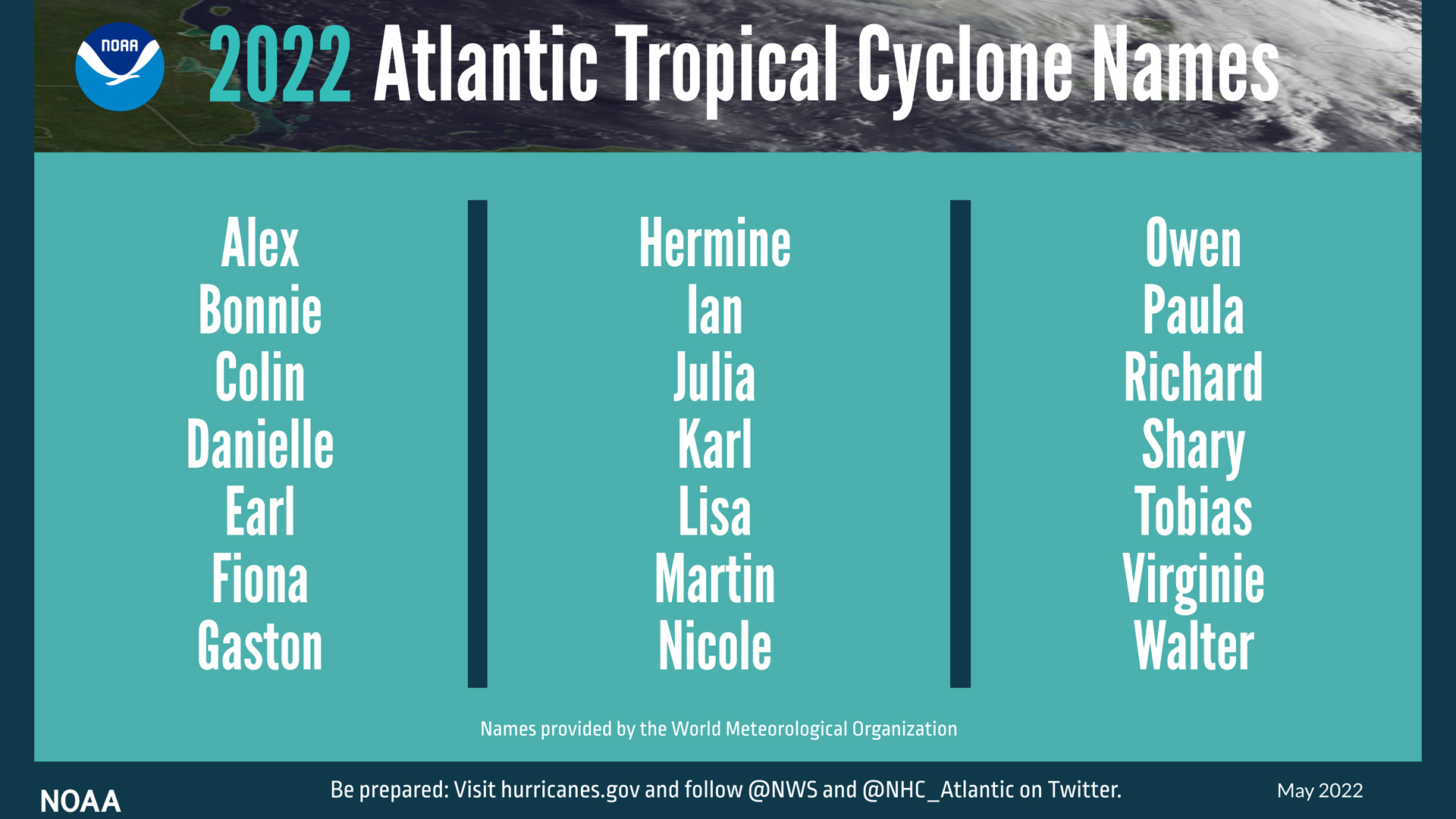

The first storm of the year will be named Alex and the next four will be named Bonnie, Colin, Danielle and Earl, according to the National Hurricane Center (opens in new tab). Only 21 names, starting with the letters A through W, are given to storms each year before Greek letters are assigned instead. The new forecast means there is a possibility that all 21 storm names will be used for the third year in a row; 21 storms developed in 2021 and a record-breaking 30 storms formed in 2020.

The current “La Niña” event, which has created warmer waters in regions of the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, is partly responsible for the above-average season forecast. La Niña, which means “little girl” in Spanish, is a climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean in which waters in the tropical eastern Pacific are colder than average and trade winds blow more strongly than usual. This can affect weather across the globe and can also lead to more severe hurricane seasons, according to NOAA (opens in new tab).

Earlier predictions from researchers at the University of Arizona (opens in new tab) on April 28 had suggested that La Niña might dissipate, meaning an only slightly above-average hurricane season. (Ocean surface temperatures are one of the main factors in fueling the size, frequency and strength of hurricanes. The warmer the water, the stronger the storm, NOAA says.)

Related: The 20 costliest, most destructive hurricanes to hit the US

Fortunately, on May 18, NOAA announced (opens in new tab) that the Central Pacific hurricane season, which also begins on June 1, is likely to be less active than average. Only two to four tropical cyclones are predicted for the Central Pacific hurricane region, compared to the average of four to five. This is because the La Niña event is causing wind patterns that will help prevent storms from growing in this region, according to the statement.

Even without the storm-inducing La Niña event, hurricane seasons have become increasingly more active as global sea-surface temperatures have risen as a result of climate change.

“We have to refocus to this new reality of dealing with this change to our environment and how it impacts us every day,” Eric Adams, Mayor of New York City, said in a NOAA press briefing (opens in new tab) on May 24 at the New York City Emergency Management Department.

(opens in new tab)

New York City was one of the areas most affected by Hurricane Ida, 2021’s largest storm, which reached maximum wind speeds of 150 mph (240 km/h), impacted nine states and was clearly visible from more than 1 million miles from Earth. By the time Ida was done, the hurricane’s winds, rainfall, storm surges and tornadoes caused an estimated $75 billion in damages, NOAA officials reported (opens in new tab) this April.

Individual storms have also become more powerful due to climate change. In February 2021, a study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters revealed that hurricane wind speeds in Bermuda have more than doubled in strength over the last 66 years due to rising ocean temperatures in the region.

The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season actually ended up being even more active than predicted. Only time will tell if NOAA’s predictions for this year are correct, but experts say people should start preparing for storms now.

“It’s crucial to remember that it only takes one storm to damage your home, neighborhood and community,” NOAA administrator Richard Spinrad said at the briefing.

Originally published on Live Science