David Glaymon is a former partner at Kynikos Associates and financial analyst.

The last US inflation report was another shocker, coming at a seasonally adjusted rate of 8.3 per cent in April. But it is the detailed expenditure category table that highlights just how tricky the situation is.

For example, consider the humble chicken, America’s most popular meat. According to the BLS report, the price of a fresh whole chicken was up 4 per cent seasonally adjusted from March, while fresh and frozen chicken parts were up 3.5 per cent. The unadjusted year-over-year price increases were 14.6 per cent and 17.9 per cent, respectively.

Similarly, egg inflation was up 10.3 per cent seasonally adjusted from March and 22.6 per cent unadjusted year-over year. We can debate what inflation came first, the chicken or the egg, but the impact on America’s poultry-loving households is undeniable.

But the inflation in chicken and egg prices highlights the Federal Reserve’s intractable position. Clearly, economic stimulus has not led to a mammoth boost in demand for scrambled eggs, chicken nuggets, hot wings and Kung Pao relative to 2019. The wave of inflation buffeting economies is to a large extent supply-driven.

The shift to a globalised, just-in-time management systems left supply chains vulnerable to the unexpected shocks from Covid-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. China’s zero-Covid policy and protracted lockdowns is now making things worse.

With few other tools to tackle this, the Federal Reserve has embarked on a series of interest rate rises to reduce demand even though the inflation issue is supply-driven. The Fed is like a patient treating a sprained ankle by punching themselves in the face.

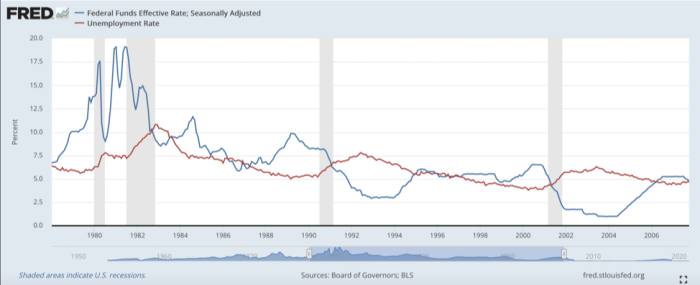

The challenge of using interest rate activity to reduce demand is that it takes roughly three-quarters of an interest rate hike to take effect within the economy. A look back at the 1978 to 2007 period shows the lag in peaks of unemployment levels to peak interest rates.

A clue to how long this supply-driven inflation has come can be found in the US Agriculture Department’s Monthly Chicken and Eggs report: In the March 2022 report, table egg production was down 1.8 per cent year-over-year.

Cal-Mine Foods, a publicly traded egg company, announced an $82mn investment on March 30th to increase its cage-free production levels, which is expected to be completed by the fall of 2023 in its Delta, Utah facility and by the spring of 2025 in its Guthrie, Kentucky facility.

The egg investment timeline is similar in many other parts of the economy. For example, look at what Jim Taiclet, CEO of Lockheed Martin indicated on the television show Face the Nation last month. He said that increasing Javelin production capacity to 4,000 per year from 2,100 “will take a number of months, even a couple of years because we have to get our supply chain to also crank up.”.

Investors want this market decline to be over, but the Fed is just at the start of its interest rate cycle, and unemployment is expected to have fallen to a pre-pandemic low of 3.5 per cent in May (non-farm payrolls are out later today). It will take some time for the rate increases to dampen consumer behaviour, given that the hottest of inflation is in consumer-related activities.

Whether it is eggs or anti-tank missiles, by then it is very likely that supply will have caught up, complicating the situation.