The £150bn energy support plan will help sooth many households fears of soaring gas and electricity bills this winter, but it has put the Bank of England on the spot with international investors watching its response closely.

The central bank’s Monetary Policy Committee will need to decide between two very different views of the economy ahead of its meeting next week to set interest rates.

First is the assertion by prime minister Liz Truss that her intervention would “curb inflation” at the same time as helping families through a difficult winter.

The alternative view, held by almost all economists, is that the additional government borrowing and spending will ultimately be inflationary and that the central bank will need to respond with higher interest rates to foster price stability over the longer term.

This latter view forms the foundation of the textbook case for a monetary authority independent of government. Left to politicians there would be a tendency to set policy to ensure pre-election booms that would stoke inflation and lead to a subsequent bust after polling day.

The delicacy of the BoE’s balancing act between orthodox economics and not being seen as obstructive to the new Truss government was illustrated on Wednesday. Efforts by governor Andrew Bailey to avoid talking about policy were interpreted as dovish act by international investors sending sterling to its weakest levels against the US dollar since 1985.

The key economic aspects of Truss’s intervention are relatively straightforward to analyse for the bank but the exact impact on the deficit remains harder to fathom.

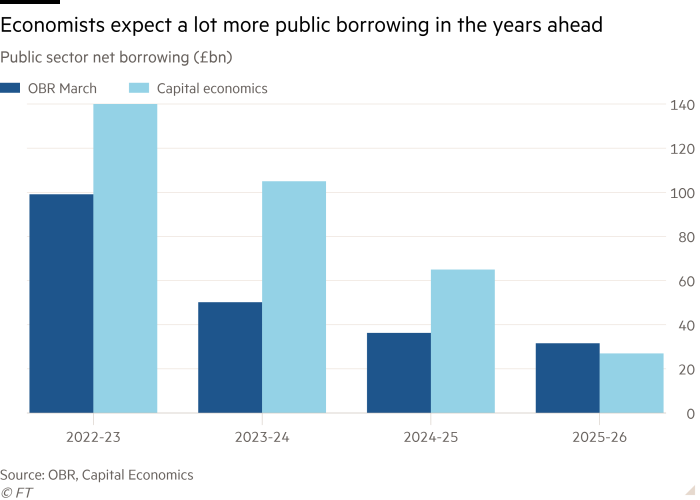

With household gas and electricity bills frozen for two years and additional support for business, few in government or in the energy community thought a gross cost estimate of £150bn over two years was very wide of the mark although the costs would vary with wholesale gas prices.

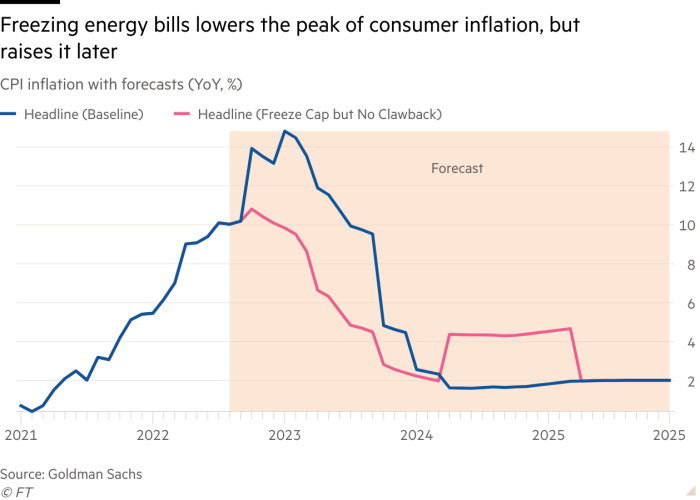

There are some offsets to this new fiscal stimulus. Economists agreed the plan was likely to lower the peak of inflation by about 5 percentage points so that instead of peaking around 15 per cent in January, it will stay at roughly the July level of 10.1 per cent before falling gradually in 2023.

In the short term, this will cut the cost of inflation-linked government debt by about £25bn, only to push it higher in the medium term because the decline in inflation will not be so steep.

There might also be further short-term savings from persuading nuclear and some renewables generators to accept long-term, fixed-price contracts that are well below current wholesale rates but are likely to come at the cost of paying too much for their electricity in the future.

The intervention means the government will borrow to cover the cost of much of the gas, with a lot of that money flowing abroad to the UK’s main suppliers in Norway, Qatar and the US. As the strain comes off household budgets, it would likely result in them spending more on other goods and services than the bank had anticipated.

This would mean a straightforward increase in demand compared with previous BoE forecasts and would reduce the severity of any recession, but it will leave the UK living further beyond its means.

Huw Pill, BoE chief economist made clear he shared that view speaking alongside Bailey on Wednesday. He said the actions of Russian president Vladimir Putin that has caused the energy crisis made the UK poorer and should the country pretend otherwise the policy would “probably lead to slightly stronger inflation” in the medium term, even if it was suppressed this winter.

He said interest rates would have to rise in response. “Will fiscal policies generate inflation? We are here to ensure that they don’t generate inflation . . . our remit is to get inflation back to target,” Pill said. “We do have work to do,” he added with the heavy implication that he favoured significantly higher interest rates.

Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist at BNP Paribas Markets, agreed the size of the intervention would “likely” cause higher inflation in future. “We think this points to more [monetary] tightening,” he added.

“The bank will need to demonstrate that it is focused on inflation — not on helping the Treasury to finance the debt,” added professor Jonathan Portes of King’s College London.

Most economists and financial market traders expect the MPC to raise rates 0.5 percentage points next week from 1.75 per cent level and reaching 3 per cent by the end of the year.

Salomon Fiedler, economist at Berenberg, a private bank, said: “Additional large-scale fiscal stimulus is problematic at a time when inflation is already extremely high.”

Kwasi Kwarteng, the new chancellor, is expected to announce a further fiscal stimulus in the form of permanent cuts to national insurance and corporation tax in a mini fiscal statement on September 19.

Truss promised the Treasury would provide further details of the costs of the energy package and the tax cuts at the same time, leaving the central bank with more to consider going into their meeting next week.