Even with Prime Minister Liz Truss’s action to stem rises in energy bills, the economic pain is just beginning.

UK households still face pressures on their finances not seen since the second world war. The same is true for companies. Caught by both rising costs and falling consumer spending, this pincer movement is troubling businesses both large and small.

So far, with spending levels still strong in the economy, many companies have been able to raise prices to mitigate the issue. They will also receive help with a cap on non-domestic energy bills this winter. Even with the underlying strengths and government support, the big question is what happens next.

This is a drama that is likely to be played out in three acts, culminating with corporate distress and a recession.

Act 1: Never-ending bills

In the first quarter of 2022, average electricity bills for companies were about 30 per cent higher than a year earlier. Rising bills have not stopped landing in the inboxes of company managers ever since.

With a crisis point having been reached in early September, the government pledged to act almost immediately to prevent companies being asked to pay up to five times their previous rates in gas and electricity charges.

It has promised to set a limit on energy bills for the next six months, with help for some smaller companies extending well into next year.

Even so, at the new controlled price, many companies will still face much higher costs for energy than a year ago.

Among the hardest-hit companies are energy-intensive industries, often at the base of the supply chain, producing metals, plastics and other parts crucial for manufacturing and building. These are now feeling the pinch. Small business confidence plunged in both the manufacturing and construction sectors this year.

Although oil prices have come off the boil in recent months, manufacturing companies that use crude oil or other fuels including gas have seen the largest rise in costs over the year to August. Gas prices have increased about 50 per cent.

For the manufacturing industry, input costs have risen 20.5 per cent in the most recent year, adding to their challenges. With food inputs also up about 20 per cent, prices of many supermarket items have naturally risen sharply.

At the other end of the supply chain, leisure industries that rely on heating large spaces, such as shops, swimming pools or nurseries, are having to turn thermostats down and put prices up. Small businesses feel they are at the sharpest end.

The squeeze is not limited to raw material costs. In much of the service sector, companies are affected more by wage increases than by higher costs.

Regular pay grew at an annual rate of 6.2 per cent in the private sector in July, the most recent month available. That was the highest rate of increase this century, excluding a period during the pandemic when the figures were distorted.

Even so, pay is growing slower than prices, which were 9.9 per cent higher in August than a year earlier, putting pressure on companies to pay more. This will be hard to resist when there are currently as many vacancies as there are people classified as unemployed, twice the normal tightness in the labour market.

In jobs in wholesale trade, construction and hospitality, advertised rates have risen sharply since the start of 2022, according to Indeed.com, the recruitment website. By contrast, advertised pay for nurses is barely rising, even after their services were in such demand as a result of the pandemic.

Act 2: Rising borrowing costs

Companies have more to be concerned about than raw material and wage costs. The cost of debt is rising too.

Having kept official interest rates close to zero for more than a decade, the Bank of England raised borrowing costs from 0.1 per cent last November and has signalled further rises to help bring inflation down. The Monetary Policy Committee set rates at 1.75 per cent in August and financial markets expect them to rise above 3 per cent by the end of the year.

Large UK companies often have fixed borrowing costs, limiting their exposure. The BoE thinks the proportion of large companies facing material risks of repayment difficulties will rise from 30 per cent to 46 per cent at the end of this year. Interest rates would have to rise to 4.5 per cent for this exposure to reach historic highs, capturing just over 60 per cent of companies. That, however, is no longer above market expectation.

Smaller companies are not nearly as well protected. While the new debt these companies took on during the pandemic was generally at fixed rates, the BoE estimates that 70 per cent of their existing stock of loans is exposed to interest rate rises within a year. Many of these companies will be exposed to a nasty borrowing costs shock in the months ahead.

At the same time, companies must look at sales. These have been falling on the high street and stress is evident in the consumer confidence figures. This fell in August to a near 50-year low as households worried about their own financial situation and the wider economy.

Act 3: Spending under pressure

Consumer spending will probably fall further. Food, rents, mortgages, petrol and energy prices, which account for more than 40 per cent of household budgets, are all rising quickly. Many consumers will cut down on discretionary spending this winter and focus on the basics. Poorer households will be forced to make even more difficult choices.

A survey of 3,000 people by SellCell, a price comparison website, showed a majority of households planning to cut down on entertainment spending and eating out. Only 24 per cent of respondents said they would not cut discretionary spending at all this winter.

Intentions to cut back do not always result in actual spending reductions, but the early evidence from the high street suggests greater spending restraint in non-food stores than in supermarkets, indicating that discretionary spending is likely to be hit.

With food manufacturers’ costs having risen about 20 per cent, the likelihood is that food price inflation will rise further from the August level of 13.4 per cent. That will put severe pressure on cafés, restaurants and food outlets to cut costs at a time when consumers are becoming much more price conscious.

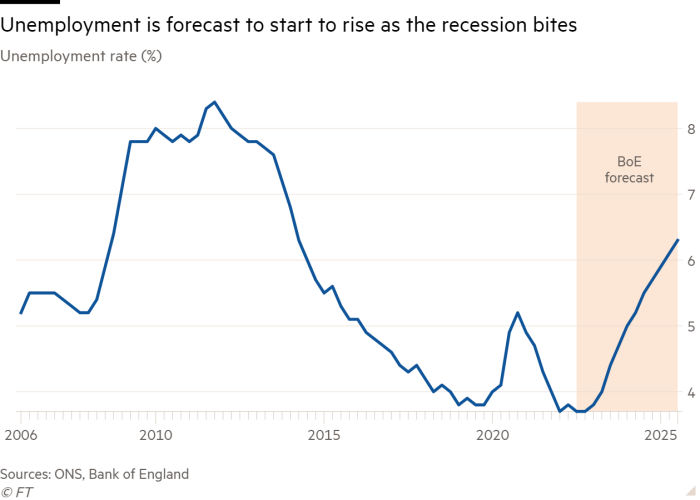

And the BoE still wants to impart a shock to ensure that inflation comes down. To the central bank, a higher rate of unemployment and lower rises in wages are the necessary evils required to restore price stability. The BoE thinks the recession will be shallow but last through much of next year, with unemployment rising to more than 6 per cent.

The data suggests the process is already well under way. Households are cutting back at the same time as corporate profits fall. Signs of corporate distress such as the 42 per cent rise in corporate insolvencies since last year are likely to rise even further.

This is how recession starts.