Just as waterfront mansions are status symbols for today’s rich and famous, ancient artificial islands in the British Isles known as crannogs may have been used by elites to display their power and wealth through elaborate parties, a new study finds.

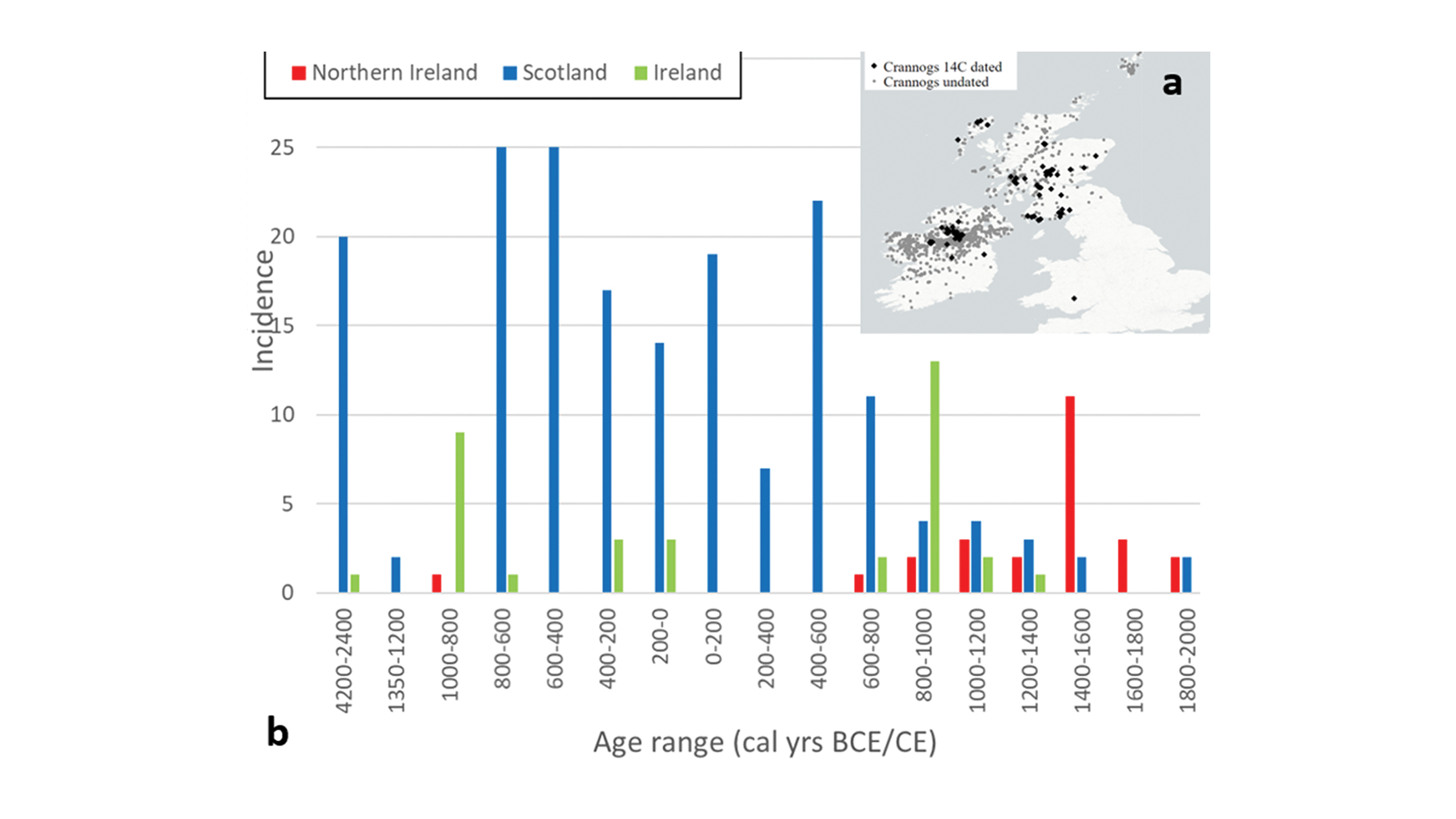

A crannog is “an artificial island within a lake, wetland, or estuary,” Antony Brown of UiT Arctic University of Norway and colleagues wrote in a study published online Wednesday (Sept. 28) in the journal Antiquity (opens in new tab). Hundreds of crannogs were created in Scotland, Wales and Ireland, between 4,000 B.C. and the 16th century A.D., by building up a shallow reef or an elevated portion of a lakebed with any available natural material — such as stone, timber or peat — to a diameter of nearly 100 feet (30 meters). A lot of trade and communication occurred along the lakes and estuaries where crannogs were built. Used as farmsteads during the Iron Age (eighth century B.C. to the first century A.D.), crannogs evolved into elite gathering places in the medieval period (fifth to the 16th centuries A.D.), according to evidence of feasting and plentiful artifacts, such as pottery, uncovered there.

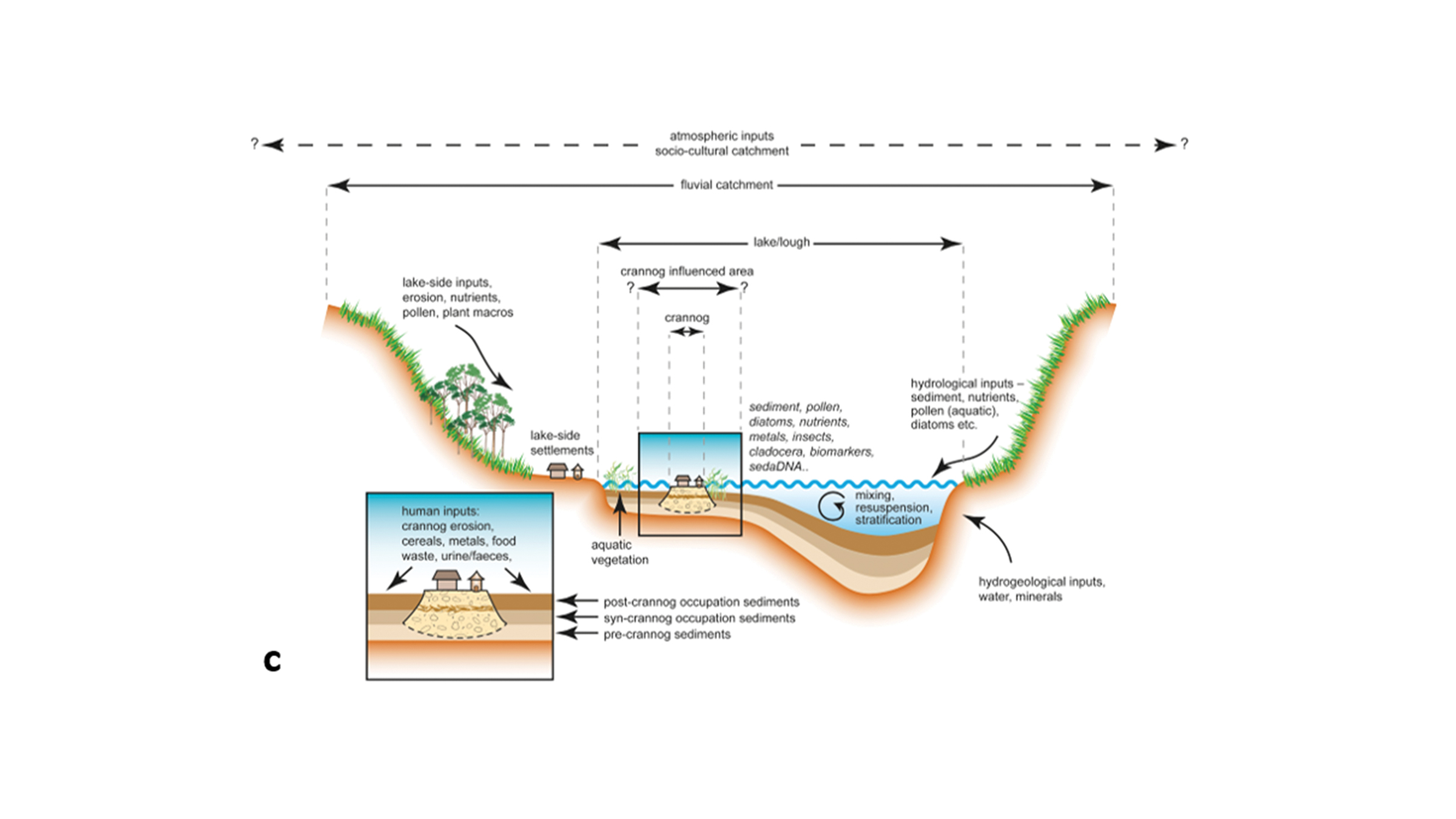

Wetland sites are much more difficult to study than those on land, so the archaeology of crannogs is a relatively new undertaking. Brown and colleagues investigated one site in Scotland (500 B.C. to A.D. 10) and two in Ireland (A.D. 650 to 1300) to better understand the purpose of these crannogs. They did it by sampling each site’s halo, or the spread of archaeological material from the center of the site.

“The lakes are shallow around the crannog; material is quickly deposited there and never washed away,” Brown told Live Science in an email.

Related: 12 bizarre medieval trends

The researchers analyzed the site halo using multiple methods, including sedimentary ancient DNA analysis (sedaDNA) — an emerging technique that enables scientists to identify all the plants and animals that contributed to the ancient environment of a site. SedaDNA analysis showed that people were cultivating cereal plants on the artificial islands, but it also revealed unusual plants like bracken (Pteridium), a type of toxic fern that was likely brought to the crannog sites to be used as bedding or roofing material, the researchers said.

SedaDNA also uncovered evidence of mammals at the sites, including domesticated cows, sheep, pigs and goats. Combining the new sedaDNA work with previous studies of pollen and animal bones, Brown and colleagues suggested they could quickly and inexpensively identify a range of activities that occurred in the past, such as animal keeping, slaughter, feasting and ceremonies.

The new study helps shed light on crannogs and their use. “Given how little we still really know about crannogs and the human activities surrounding them, the methods and results described here are very interesting,” said Simon Hammann, a food chemist at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg) in Germany who was not involved in the study. Last month, Hammann and colleagues published a study in the journal Nature Communications (opens in new tab) on the presence of wheat in pottery residue at Neolithic crannogs in Scotland. Soil conditions do not support bone preservation at the sites Hammann works at in the Outer Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland, so he found the work of Brown and colleagues very compelling.

“Inferring specific activities such as feasting is always difficult,” Hammann told Live Science in an email, but “in combination these methods seem to draw quite a conclusive picture.”

The pollen sedaDNA data are also important because they “offer new approaches to the study of human-plant interactions that are not possible using traditional pollen techniques,” according to Don O’Meara, science advisor at Historic England, a British historical preservation agency. In an email to Live Science, O’Meara, who was not involved with the new research, pointed out that the sedaDNA technique provides information only on the plants growing locally, while traditional pollen analysis may not be able to distinguish local plants from those transported by wind or water from many miles away.

Related: 17 people found in a medieval well in England were victims of an antisemitic massacre, DNA reveals

Factors like glacial melting and coastline destruction can threaten archaeological sites, and extensive excavation at these sites is often impossible. The sedaDNA approach “has the potential to be adapted to other archaeological wetland sites,” Ayushi Nayak, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology in Germany, pointed out in an email to Live Science, meaning scientists could glean information that would otherwise be inaccessible from vulnerable sites.

The reason for the abandonment of the three sites that Brown and colleagues studied is still unknown. One tantalizing bit of evidence comes from Lough Yoan South in Ireland, where the team found two whipworm parasite eggs on the floor of the crannog there. Brown confirmed by email that these eggs are what remains of human excrement, deposited around the time the crannog was abandoned.

No other human DNA or remains — such as bog bodies — have been found at crannog sites, though.

Crannogs “were very much places for the living,” Brown said.

Originally published on Live Science.