Office workers across the world’s biggest economies have not resumed their pre-pandemic commuting, instead embracing hybrid working as the new normal according to widely-watched commuting data.

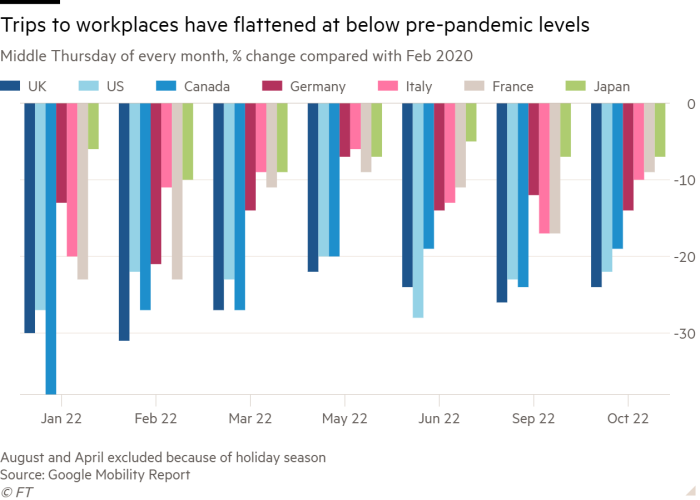

By mid-October trips to workplaces in the world’s seven largest economies were still well below their levels before the coronavirus took hold in early 2020, according to a Financial Times analysis of phone-tracking movements published by Google.

In Japan, footfall was 7 per cent below pre-pandemic levels while in the UK it was down 24 per cent. Across major advanced economies office trips are more popular on the middle days of the week, while Monday and Friday tend to show large drops in attendance.

Cities which host financial and business districts saw a larger loss of office footfall than in other major population areas, according to the Google figures.

Economists said the shift towards remote working had become the new normal.

“Working from home will ultimately stick,” said Cevat Giray Aksoy, an economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development who has researched the trend. “Workplace-related mobility levels will remain lower than the pre-pandemic levels.”

The big shift to working from home “presents challenges for dense urban centres that are organised to support a large volume of inward commuters and a high concentration of commercial activity”, said Aksoy.

Aksoy’s research found a rising share of job postings in many countries offer employees the opportunity to work remotely one or more days per week. Sara Sutton, founder and chief executive of FlexJobs, a careers service specialising in remote and hybrid jobs, agreed.

“We have definitely seen a tipping point towards a deeper and more permanent integration of remote and hybrid work into organisations,” she said.

Survey data suggest that people like working from home and the practice helps to lower firms’ overheads and carbon emissions, but evidence on the impact on productivity is mixed.

The Freespace index, which tracks office usage in big corporations around the world, shows that occupancy is about half its 2019 levels for both workspace stations and meeting rooms. Kastle data, which tracks fob access to US offices, particularly in big professional services businesses, shows that occupancy only returned to about half of pre-pandemic levels in mid-October.

A survey by the Munich-based think-tank Ifo showed that in August one-quarter of employees in Germany still worked from home for at least part of the time.

In the UK, a regular survey run by the Office for National Statistics showed that more than a fifth of UK workers were using a hybrid model of working in early October, largely unchanged since the spring. The proportion rose to more than half of the workforce for information and communication, with professional, scientific and technical activities being only a little lower.

Google began to publish daily data on travel patterns in April 2020 as a tool for governments and policymakers to track the effects of Covid restrictions on the economy. It initially showed a collapse in visits to workplaces as people in many countries were forced to stay home.

The mobility reports were used by the Bank of England and the European Central Bank as a snapshot of the impact the pandemic was having on the economy, as they were published months ahead of official figures.

The data was a “fantastic” proxy for economic activity, said Bert Colijn, economist at ING. The daily count of trips to the workplace also provided one of the best indicators globally to show how incomplete the return to the workplace had been, he said.

But as post-pandemic commuting patterns have become established, Google will not update the series further from now on.