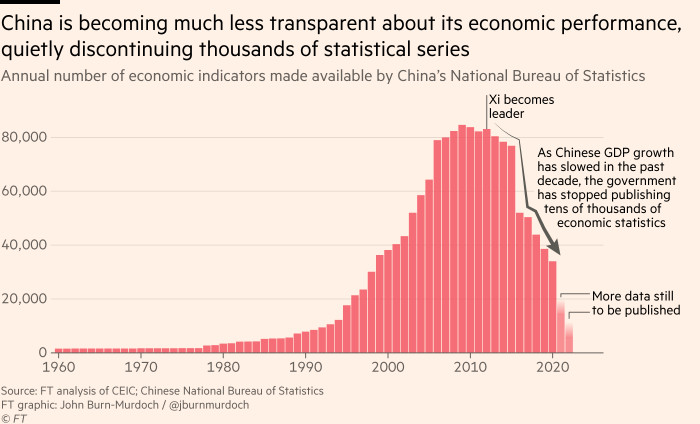

If you had paid a visit to China’s National Bureau of Statistics in the days following Xi Jinping’s election as general secretary of the Chinese Communist party in 2012, you would have found a cornucopia of economic data.

The number of people employed in the outdoor playground amusement equipment sector, natural gas exports from Guangdong to other provinces, the electricity balance of Inner Mongolia. You name it, they published it, along with more than 80,000 other time series.

But just one year later, those three series and thousands more were no longer updated. Skip to 2016, and more than half of all indicators published by the national and municipal statistics bureaus had been quietly discontinued. The disappearances have been truly remarkable.

Viewed against this backdrop, this week’s decision to indefinitely delay the publication of headline third-quarter indicators, including gross domestic product, looks less like a surprise: it continues a trend towards statistical opacity as China shifts from sustained high growth to more modest numbers. The blackout is just one of many signals that whatever number does finally emerge is unlikely to be high — and it may be treated with scepticism in any case.

Aside from the fact that one does not typically hide evidence of good performance, many of the more granular discontinued data series were previously used by analysts to check against China’s headline indicators, frequently finding the GDP figures overstating performance. We are left with increasingly unconventional indicators to gauge China’s current performance. It doesn’t look good.

In striking recent research, Luis Martinez, an economist at the University of Chicago, used data on night-time light intensity from satellite imagery to show that Chinese GDP growth over the past 20 years may have been about a third slower than reported each year, leaving its economy significantly smaller than the US, rather than slightly larger.

As for the real-time indicators we have grown familiar with during the pandemic, such as public transport use, road congestion and flight volumes, they offer a reason for China’s GDP figure no-show. With almost one in five of its over-80s still unvaccinated, compared to about 7 per cent in the US and virtually zero in the UK, China’s pursuit of zero-Covid is putting sustained downwards pressure on output. Closer to pre-pandemic activity levels than any other country in early 2021, China is now among the laggards, operating about a third lower than normal.

Based on the relationship between previous, published Chinese GDP figures and data collected by the Economist, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and flight-tracking site Airportia, I estimate that China’s third-quarter growth figure will be about 3 per cent, significantly down on the 5.5 per cent target, and at the low end of recent forecasts. Apply Martinez’s satellite-based adjustment for exaggeration, and that becomes 2.7 per cent, just half of the target.

If reality falls so far short of expectations, we may see another swath of Chinese economic statistics vanish.