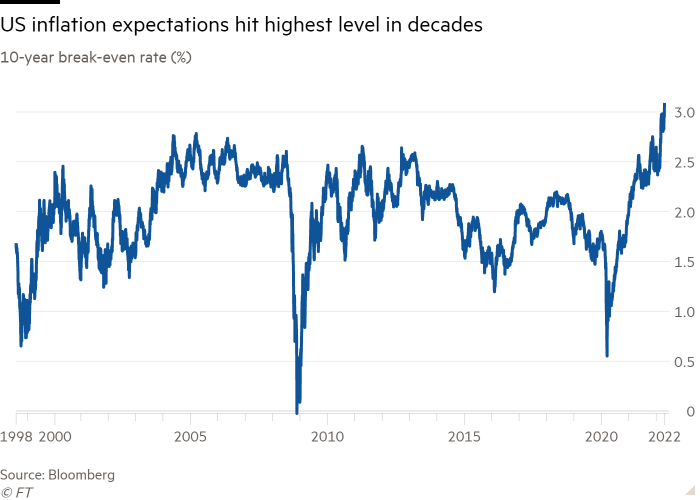

Investors’ expectations for US inflation have shot to their highest level in decades even as the Federal Reserve signals an aggressive tightening of monetary policy is imminent, underscoring the challenge central banks face in convincing markets they can tame runaway price growth.

A historic bond rout has intensified this week as officials from both the Fed and the European Central Bank stepped up their inflation-fighting rhetoric. But the hawkish message has done little to arrest a rise in long-term inflation expectations, which are watched closely by central bankers concerned that they can become self-fulfilling.

The US 10-year break-even — a closely watched gauge of market inflation expectations over the next decade — climbed to 3.08 per cent on Friday, the highest level in at least two decades. Break-evens measure the difference in traditional US government bond yields and those on inflation-adjusted Treasuries.

Janet Yellen, Treasury secretary, and a former Fed chief, acknowledged on Friday that the period of elevated inflation would probably last “for a while longer”, although she said the rate of price growth may have peaked.

Yellen’s comments came after Jay Powell, Fed chair, said on Thursday that “it is appropriate in my view to be moving a little more quickly” to combat inflation, which is running at the fastest pace in 40 years, and sent his strongest signal to date that the central bank is prepared to deliver a half-point interest rate increase at its next policy meeting in May.

“Central bankers seem to be at this point of maximum pressure on inflation,” said Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at BlueBay Asset Management. “The market is giving the message that you were complacent on inflation for too long, it’s time to get on with it.”

Markets are now pricing in extra-large 0.5 percentage point rate rises at each of the Fed’s next three meetings, with speculation about an even larger 0.75 percentage point adjustment brewing.

Krishna Guha, a former Fed staffer who is now vice-chair at Evercore ISI, said the likelihood of that kind of move was “still very low”, but added the central bank needed to communicate more clearly about its approach to setting monetary policy.

“When Fed officials sound more hawkish . . . market participants perceive increased concern on the part of the Fed about the medium-term inflation outlook and update their own beliefs accordingly,” he said. “So inflation break-evens increase rather than decrease on the hawkish shift, which in turn pushes Fed officials to sound more hawkish, chasing their own tails.”

Powell on Thursday also suggested the Fed may need to raise interest rates to a level that actively begins to constrain growth, but pushed back on the idea that the Fed will need to provoke a sharp recession in order to bring inflation back to its 2 per cent target. He affirmed that a “soft landing” for the economy remained the central bank’s goal.

That message has left some investors wondering whether the Fed will allow inflation to remain elevated for longer, according to analysts at Barclays.

Very high inflation expectations in markets are in part a reflection of the current rate of consumer price rises in the US, which reached 8.5 per cent in March following a surge in the cost of energy and food. But even five-year five-year inflation swaps, a different measure favoured by central bankers that strips out current inflation levels and looks at the second half of the next 10 years, have hit their highest point since 2014 at 2.84 per cent.

The picture is similar in the eurozone where five-year five-year inflation trades at 2.45 per cent, the highest since 2013. ECB president Christine Lagarde suggested on Thursday that the bloc’s bank will be less aggressive than the Fed in acting to tame inflation as she appeared alongside Powell at the IMF panel.

Still, recent comments from some the ECB president’s colleagues have alerted markets to the possibility of earlier tightening than previously thought. Vice-president Luis de Guindos said earlier this week that a rate increase — the ECB’s first since 2011 — could come as early as July.

German two-year bond yields, which are highly sensitive to ECB rate expectations, climbed to their highest level since 2013 on Friday.