The European Central Bank has issued a mea culpa for persistently underestimating inflation, blaming its increasingly large forecast errors on soaring energy prices, supply chain bottlenecks and a faster economic rebound from the pandemic.

The ECB said in a paper published on Thursday that it had tried to learn from its mistakes by improving its models. But it warned that the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the further lifting of Covid-19 restrictions meant that inflation would “remain very challenging to forecast in the near term”.

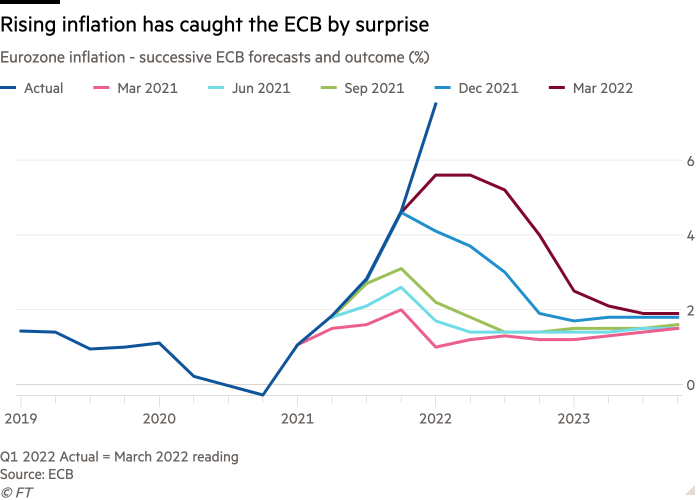

Inflation has consistently risen faster than the ECB predicted for the past year, hitting a eurozone record of 7.4 per cent in March, and stirring up criticism, even from members of the central bank’s own governing council, about the weakness of its forecasting models.

Data published on Thursday showed German inflation increased to a new 40-year high of 7.8 per cent in April, while Spanish inflation fell from a 37-year high owing to lower electricity and fuel prices.

The ECB made its worst ever inflation forecast in December when it predicted eurozone consumer price growth would fall to 4.1 per cent in the first quarter of this year. Instead it shot up to 6.1 per cent, prompting the ECB to accelerate its plans for stopping net bond purchases and opening the door to a potential interest rate rise as early as July.

The ECB’s inflation target is 2 per cent.

Eurostat is on Friday due to publish its flash estimate of eurozone inflation in April, which is expected to remain close to March’s record level. Luis de Guindos, ECB vice-president, said on Thursday that the peak of eurozone inflation was “very close” and predicted it would decline in the last six months of this year.

The ECB said its poor record in forecasting inflation was mostly due to “unexpected developments in energy prices, coupled with both the effects of reopening following the removal of coronavirus-related restrictions and the effects of global supply bottlenecks”.

Wholesale gas increased more than six times in the year to the fourth quarter of last year, while wholesale electricity prices rose almost fivefold in the same period. “The exceptional increase in energy prices was largely unanticipated by market participants,” it said, adding that its assumptions were set “according to market-based futures”.

The impact of wholesale energy prices on consumer markets had come much quicker than it expected too. “For electricity, wholesale prices were passed on to consumers almost immediately in some countries, despite this pass-through historically having taken three to twelve months,” it said.

For many years, the ECB had overestimated future inflation, but Thursday’s paper said its underestimation of price growth started in the first quarter of last year and had “become more pronounced since the third quarter of 2021”.

But it added that “international institutions and private forecasters have recently made similarly large errors” and its record was no worse than those of the US Federal Reserve and Bank of England. The Fed stopped insisting inflation was “transitory” last November. Unlike the ECB, both the Fed and the BoE have raised rates in response to price pressures.

The ECB said “recent developments imply the need for a more detailed assessment of the energy market”, adding that it had updated its models to include separate assumptions for wholesale gas and electricity prices to account for their recent decoupling from oil prices.

Inflation in Germany was 7.8 per cent in April, up from 7.6 per cent in March, according to an estimate published on Thursday by the federal statistical agency, which said growth in energy prices slowed to 35.3 per cent, down from 39.5 per cent in the previous month.

Spain’s statistics office estimated inflation in the country fell in April to 8.3 per cent, down from 9.8 per cent in March, which was its highest level since 1985. But core inflation in Spain, excluding energy and processed food prices, continued to rise to a 27-year high of 4.4 per cent.

Markus Gütschow, an economist at Morgan Stanley, said the ECB “may take some relief” from signs that inflation is nearing its peak, which “could take some pressure off to hike as early as July . . . but the fact that core pressure continues to build is clearly a worrying sign for policymakers”.